Where Art Meets Nature

CONTEMPORARY MODERN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

Vita brevis.

painting, culture, architecture, contemporary, music, history, and nature

VISION

CONTEMPORARY MODERN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

WALTER RYU STUDIO is dedicated to pushing the boundaries of modern landscape architecture. We believe there is a lot of work to do for communities. Through collaborative design, we can help enhance their living quality and upgrade their artistic environment. Our team of innovative designers and environmental experts collaborate to create sustainable and visually striking landscapes that integrate seamlessly with contemporary urban spaces. With a focus on blending art, technology, and nature, our projects redefine how people experience and interact with their environment.

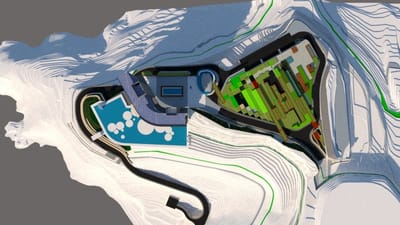

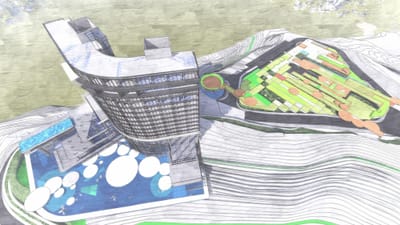

*Example_The Okpo Hotel and Resort 2022 : The existing shipyard culture inspired the design language and reused material on the parking lot structure and landscape element design. This created a strong visual identity and sustainable elements, giving a long-lasting impression to visitors and an eco-friendly design.

ABOUT

Our primary interest is to create a genuinely designed product while respecting the space's environmental impact on communities as they heal their day-to-day lives.

Walter Ryu, ASLA, RLA, is an award-winning registered Korean American landscape architect with 32 years of professional experience in design and project management, strong expertise in design and construction, and a background in landscape architecture, urban design, planning, and civil engineering.

Walter was one of Glenn Murcutt's graduate students, who later received the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize. Influenced by Murcutt’s philosophy of site-sensitive design and modern architecture, Walter continues to integrate these principles into his landscape practice, emphasizing harmony between architecture, nature, and human experience.

After completing his study under James Corner (New York Highline project designer and 2023 ASLA Design Medal recipient) at the University of Pennsylvania in 1994 with a Master’s degree, he was fortunate to collaborate with many notable landscape architects, such as Michael Vergason and the late Mr. James van Sweden from Oehme, van Sweden and Associates, in Washington, D.C. At Oehme, van Sweden, he worked on major design projects, including the Chicago Botanic Garden in Illinois and the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. His mentor, James van Sweden, received the ASLA Design Medal, the highest individual honor from the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA), in 2010.

Before transitioning to Asia in 2008 to pursue continued design experience and further career growth in landscape architecture, he ran his own firm in Virginia for six and a half years, designing many high-end luxury residential landscapes while enhancing his skill set in design details and project management. He won two awards from the Tri-State Contractors Association for the residential design-build categories. It was a remarkable achievement for the minority firm to compete with larger firms in two years.

While learning from a notable American landscape architect, Mark Mahan, in Singapore, he encountered additional international projects in India, the UAE, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, and China. He learned from Mark Mahan, who designed the Four Seasons Hotel and Resort in Bali, Indonesia. The design collaboration experience was enhanced further with Cicada Ltd. The firm won the most prestigious Singapore Presidential Award as the first LA designer.

Having completed multiple luxurious hotel and residential projects, he collaborated with Hassell, the largest architecture firm in Australia at the time. He and his team received the 2016 Australian national LA Award of Excellence in the International Design category for the Nanjing Tangshan Geological Museum in China.

The E Land Group, one of the largest retail giants in Korea, scouted him to design and build *the Kensington Saipan Hotel and Resort in 2015. He was stationed in Saipan for almost a year while studying tropical plants, and he performed design and construction tasks himself, in collaboration with the site team, to successfully deliver three water features and plantings.

He joined Heerim Architects and Planners, Korea's largest architectural firm, to serve as Head of LA Design for their first Landscape Architecture Design team in Seoul, South Korea. He has won international competitions, including the KBS Future Broadcasting Office and the Korean Embassy in Australia.

Having briefly collaborated with ASPECT Studios in Shanghai, he decided to further explore opportunities in larger-scale public works and mixed-use commercial projects. He collaborated with AOYA L&A, the largest landscape architecture firm in China, as a design director at its headquarters in Shenzen before the outbreak of COVID-19.

*The Kensington Saipan Hotel project was published in the July issue of Landscape Architect and Specifier News magazine, 2021, for the Hotel and Resort special issue.

In 2025, Walter Ryu Studio was selected as one of five landscape architecture firms in Georgia in a LASN magazine special issue titled "LA Firms in the South."

Walter Ryu Studio delivers creative, innovative Landscape Architecture solutions in the Atlanta, Houston, and Miami metro areas, as well as other suburban communities in Georgia, Texas, Florida, Virginia, and Maryland.

AWARD

- AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS INTERNATIONAL PROJECT OF EXCELLENCE

- HONG KONG INSTITUTE OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS SILVER AWARD (HIGHEST HONOR)

- RESIDENTIAL LANDSCAPE DESIGN BUILD MERIT AWARD (WASHINGTON D.C. MARYLAND, VIRGINIA ,USA)

- SINGAPORE UNIVERSAL DESIGN MARK AWARD

- URBAN LAND INSTITUTE GLOBAL AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE FINALIST

- INTERNATIONAL PROPERTY AWARDS (ASIA PACIFIC) BEST RETAIL ARCHITECTURE

- LUXURY HOTEL AWARD

- SINGAPORE’S LEADING RESORT AWARD

- THE INTERNATIONAL HOTEL AWARD

PUBLIC

PRIVATE

URBAN DESIGN

PARKS AND GARDENS

CURINGA ITALY GARDEN

A Dialogue Between Past and Present The Curinga Italy Garden is a landscape architecture project grounded in the principles of minimum impact design and multi-use spatial planning. Curinga, Italy (2024)

Learn MoreJAMSU BRIDGE PARK CONCEPTUAL DESIGN

Jamsu Bridge Conceptual Design Competition, Seoul, Korea (2023)

Learn MoreBUONA VISTA METRO GARDEN IN SINGAPORE

Buona Vista Metro Garden in Singapore is a lush urban retreat, offering serene green spaces for relaxation and recreation amidst the bustling city. Ideal for families, nature enthusiasts, and professionals seeking a peaceful escape.

Learn MoreCHUNHU SPRING LAKE PARK

This project is located in Kunming City, China. It is the great opportunity to provide a community park for the new development.

Learn MorePUBLICATION

We are thrilled to announce that we will update more projects on the book soon!

Read MoreLandscape Architect magazine in US featured the Kensington Hotel & Resort in the July issue of Hotel and Resort special Issue. The Saipan Island is one of the hottest tourist destination in the world!

Read MoreA numerous press released the successful green roof design news of the supreme court of Korea on Jan 5, 2022.

Read MoreBLOG

Reflections on the Atlanta BeltLine and how its circular form demonstrates the power of landscape architecture to create a cultural platform that connects communities, public space, and urban life.

Read MoreA reflective essay from my visit to Chiang Mai exploring natural materials in architecture and the inspiring action-driven journey of Markus Roselieb, founder of Chiangmai Life Architects. A personal perspective on bamboo, sustainability, and practicing design across cultures.

Read MorePollinator gardens play a vital role in supporting biodiversity and promoting ecological balance. In the blog post 'A Different Perspective on Pollinator Gardens,' the author explores alternative viewpoints on how aesthetics, functionality, and plant diversity can harmoniously coexist to foster habitats for pollinators. By creating a space that is not only beautiful but also environmentally impactful, readers can gain insights into designing gardens that benefit wildlife and promote sustainability. This article invites you to think creatively about gardening practices and their larger ecological significance.

Read MoreThis blog explores how impromptu conceptual sketches in landscape architecture mirror the spontaneity of music improvisation—revealing the value of intuition in design and the limits of AI in capturing creative spirit.

Read MoreHow community participation, flexibility, and everyday life shape truly successful public spaces — exploring the Fourth Plinth in London and the riverfront alley in Vientiane, Laos.

Read MoreA reflection on how life’s journeys—across countries, challenges, and dreams—shape creative work, inspired by the stories of Cervantes, baseball pitcher Chris Martin, and my own career in landscape architecture.

Read MoreDesign a residential garden needs a vision for the designer.

Read MoreIntroduction; Walter Ryu’s Landscape Art & Architecture: Thoughts and Story

Read MoreCONTACT

ATLANTA 8735 Dunwoody Place Atlanta, GA 30350 O. 470 208 7628 MIAMI 1065 South West 8th St. Miami, FL 33130 O. 786 807 8778 SEOUL 257-46 Guei Dong Gwanjin Gu Seoul, Korea 05043 O. 82 2 457 7815